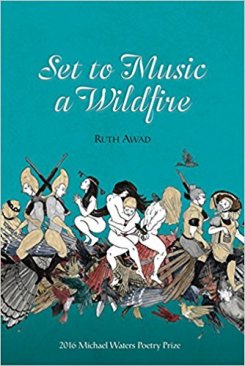

In November of 2017, Shelly Weathers interviewed Ruth Awad for SHANTIH Journal, issue 2.2, which showcases a number of poems from Ruth’s recently published book, Set to Music a Wildfire. Speaking of Ruth’s new work, Maggie Smith said:

“The story Ruth Awad tells in this gorgeous debut collection is one of history and memory, displacement and estrangement, and perhaps above all, imagination and empathy. It’s the story not only of the Lebanese Civil War—the sky ‘unzipping,’ the ‘whistling bombs you couldn’t see coming…the beehive rounds, whirring metal wings,’ the ‘woman with half-singed hair…her breath like a sizzled wick’—but also of a family in America and the struggles that continued here. Awad approaches the story—of a country, a man, a family—as if excavating priceless artifacts and holding them up to the light. You will want to lean in close to see them, in all their rich, chilling, and tender detail.”

Shelly’s conversation with Ruth centered on the inspiration for her work, a closer look into a number of her poems, and — of course — her amazing dogs. We could not be prouder of our opportunity to showcase her work.

Shelly Weathers: As a poet, what is your goal, your hope in terms of your body of work?

Ruth Awad: This is a lofty, lifelong goal, but I hope my work helps make sense of the chaos and heartbreak and awe that surrounds us. That’s at least what I’m trying to do.

SW: How do place and family influence your work?

RA: I think you should always write about what matters to you. So it makes sense that my family will keep showing up in and influencing my work. They even influence what I don’t write, at least for now. I try to be mindful of our collective experiences and let them read drafts that share those stories.

As for place, it’s hard to separate place from my point of view. I grew up mostly in the Midwest, and the people and attitudes of those places leave their fingerprints, even if I’m not directly writing about them. And when I do I write about specific places, I think of it like the establishing shot of a film. It grounds the reader and gives texture.

SW: Let’s bring that idea closer—how do you approach understanding your intentions within a single poem?

RA: I rarely start writing a poem without having a general idea of what it’s about and what I’m trying to accomplish. Revision is usually where I polish up that initial idea.

SW: Moving further into the specific, we’d like to look at some of the poetry featured in this edition of SHANTIH Journal. In “Interview with My Father: Names,” the names of the dead are written into slips of paper, which is both a literal description of a ritual and a metaphorical transformation. In “The Green Line,” bullet holes have mouths, Lebanon, a line of broken vertebrae. What is caught in this exchange, the transformation from and the acquisition of physicality?

RA: I think the physical helps ground and edify complex feelings (fear, grief) and situations (death, war). There’s also this idea of permanence when it comes to the physical, right? This sense of, If I can hold it, I can keep it. That’s why we mark our losses with physical objects: monuments, gravestones, etc. It’s our way of tying what was lost to the world we still experience and exist in. And in that way, we can hold onto and return to it. Those are similar ideas to what’s at work in these poems.

SW: In “Chimera,” from which the title of your collection is taken, the poem shifts and changes with the possible interpretations of its name. I read it as a family poem, a piece about the possibility and impossibility of individuation, but it can be read as a love poem that explores the monstrous nature of passion—and those are only two possible ways to read this out of many. How do you choose to view this metaphor?

RA: It definitely deals with romantic love and, as you pointed out, the struggle and necessity of individuation. It could be considered a love poem to the self: a reflection on a toxic, consuming relationship and an acknowledgement of the growth that came from it.

SW: How do you choose your metaphors or do they emerge as you write or revise?

RA: They usually come to me as I write. I tend to think literally and linearly, so metaphors are something I have to work at and then revise so they don’t feel forced.

SW: “The Dead Walk Over Your Land” is a favorite of mine. I read it as a haunting of myth, of family, of familial myth. At the end of the poem, you say, “they are all with you” – the myth, the flood, the animals, the things your grandmother told you, the weight of your mother at the foot of your bed – why must that be so? Is home, by necessity, a ghost story?

RA: Oh, I like that idea a lot. The idea of “home” has been an elusive thing for me – I moved around a lot growing up, my parents’ divorce meant going back and forth between different houses and parenting styles, and I’ve witnessed my dad’s feelings of displacement throughout my life. That’s a long way of saying, I think we’re all haunted by where we come from, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

SW: I know that poems are like children and you shouldn’t single out one, but I can’t help it if I fall in love. There is something so tender in the balance between the grace and the mercilessness of memory and knowledge, in careful, equal measure—or so it seems to me. Do you have favorites among your own work? What do you look for in a poem that makes it feel successful?

RA: That’s a great question. Right now, “Let me be a lamb in a world that wants my lion” is probably my favorite poem, but it’s also one of my more recent ones. I find I’m most starry-eyed over whatever I’ve written last because it’s still got its claws in me.

As for what makes a poem feel successful, it’s a very intuitive, gut-driven process for me. I know if I am moved by the poem, I’ve probably written something that will resonate with others, too. I go after the feeling first and refine later, usually.

SW: There are a few questions we always love to ask: What first drew you to poetry?

RA: I’m a control freak! Okay, but seriously, there’s something appealing about the level of control you can exert over a poem: you have the freedom to write about anything (well, almost), you have endless formal choices, you can shape how the poem looks on the page, you choose the line breaks, and you can build the poem word by word. In short, I love the precision of poetry.

SW: What work is foundational for you or first inspired you? Whose work are you currently reading?

RA: The first book of poems I ever read was Sylvia Plath’s Ariel. My mother gave it to me for my 12th birthday, and it lit me up. I will probably always be inspired by the sparse way she uses image and by her honesty.

I’m reading so much good stuff lately: Beast Meridian by Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, Electric Arches by Eve Ewing, The Patient Admits by Avery Moselle Guess, the magic my body becomes by Jess Rizkallah, Still Can’t Do My Daughter’s Hair by William Evans, and I’m super excited about Hanif Abdurraqib’s collection of essays They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us. I think everyone should read these books.

SW: What is your process like? Is writing a practice that you schedule or is it all about the muse and the moment?

RA: A little of both these days. I work a 9 to 5 gig (for an insurance agency, no less!) that leaves me pretty cognitively beat by the end of the day. So I try to spend my off-hours during the week reading and then carve out time for writing (or at least trying to) on the weekends. I am one of those types who can’t stand a soulless draft, so if the magic isn’t there when I’m trying to write, I shelve it and come back to it when I have something worth saying.

SW: Do you have a publication philosophy? How important is it to publish, to read and share your work?

RA: I think a poem is meant to be shared and to engage an audience. So if you are doing the work, share the work. You never know who you’re going to reach, and it could be a necessary, life-giving exchange (that’s been true for me – poems have given me a language for many of my experiences).

To tackle that question from a pragmatic angle, if you’re trying to make a career of poetry, of course publishing is important. But that doesn’t mean it’s everything. I’d even argue it’s better to carefully place your poems with journals that align with your values than to just get a poem placed wherever.

SW: Beyond your poetry as a body, you’ve done a lot of work examining poets and their pets. What have you learned through that process?

RA: Namely that creating poems is emotional labor and many poets have found their pets take some of the edge off that process. It also seems like a lot of poets are eager to talk about this relationship and to honor it. I’m glad to give a small place for that to happen.

SW: For our final question, what do you wish we had asked you?

RA: I’m always happy to talk about my dogs. I wish you’d asked me why they are so cute so I can say in earnest that it’s because they are made of CLOUDS and DREAMS.